Section 7: Post-Mortem Forensics - Traffic Analysis

| Course Overview | Return to Section 6 | Proceed to Section 8 |

Section 7: Post-Mortem Forensics - Traffic Analysis

7.1. Introduction

In many respects, the realm of network packets is the ultimate domain for threat hunting. It is the only place where malware cannot hide, at least not if it intends to actually communicate or transfer data. Thus, even if malicious traffic is buried under an avalanche of legitimate traffic, one thing is for sure: the malware’s communication is always present, somewhere.

Traffic analysis is an absolutely integral part of threat hunting, playing a major role in nearly every aspect — whether you are searching for initial evidence or seeking to build a case. Accessing packets directly using tools like WireShark/Tshark, or employing specialized software such as Zeek or ACHunter (RITA), provides incredible opportunities for threat hunters.

In this course, however, we are only going to touch on it lightly. The reason for this is simple: we have simulated a very specific phase of being compromised. We emulated a stager reaching out to establish a C2 connection, and even though we briefly touched on some other actions, we severed the connection shortly after it was created.

In other words, we actually performed the initial exploitation (i.e., creating the connection), but we largely skipped the ‘post-exploitation’ phase. Beyond all the details, the major difference between these two phases often relates to duration: while initial exploitation is typically brief, post-exploitation can last weeks, months, or even years.

So here’s the thing: traffic analysis is fundamentally about recognizing patterns. But meaningful patterns generally emerge over time. For example, let’s say a C2 beacon reaches back to the C2 server every 20 minutes. If you only had a one-hour packet capture, you would expect to see only three callbacks, which is an insufficient sample size to derive patterns from. Conversely, if you had a one-week packet capture, you could expect to see close to 150 callback packets, likely forming a discernible trend in terms of packet size and duration between sends.

All this to say: although traffic analysis is incredibly important for threat hunting, due to the specific nature of the attack we emulated here, it isn’t an ideal match in this context. Nonetheless, I wanted to introduce it in a rudimentary sense in this course so that you have some exposure to what can be expected regarding an initial exploitation, even if it’s minimal. The next course we’ll do will be all about traffic analysis, so rest assured you will get an opportunity to get much more familiar with this powerful approach to threat hunting.

7.2. Analysis

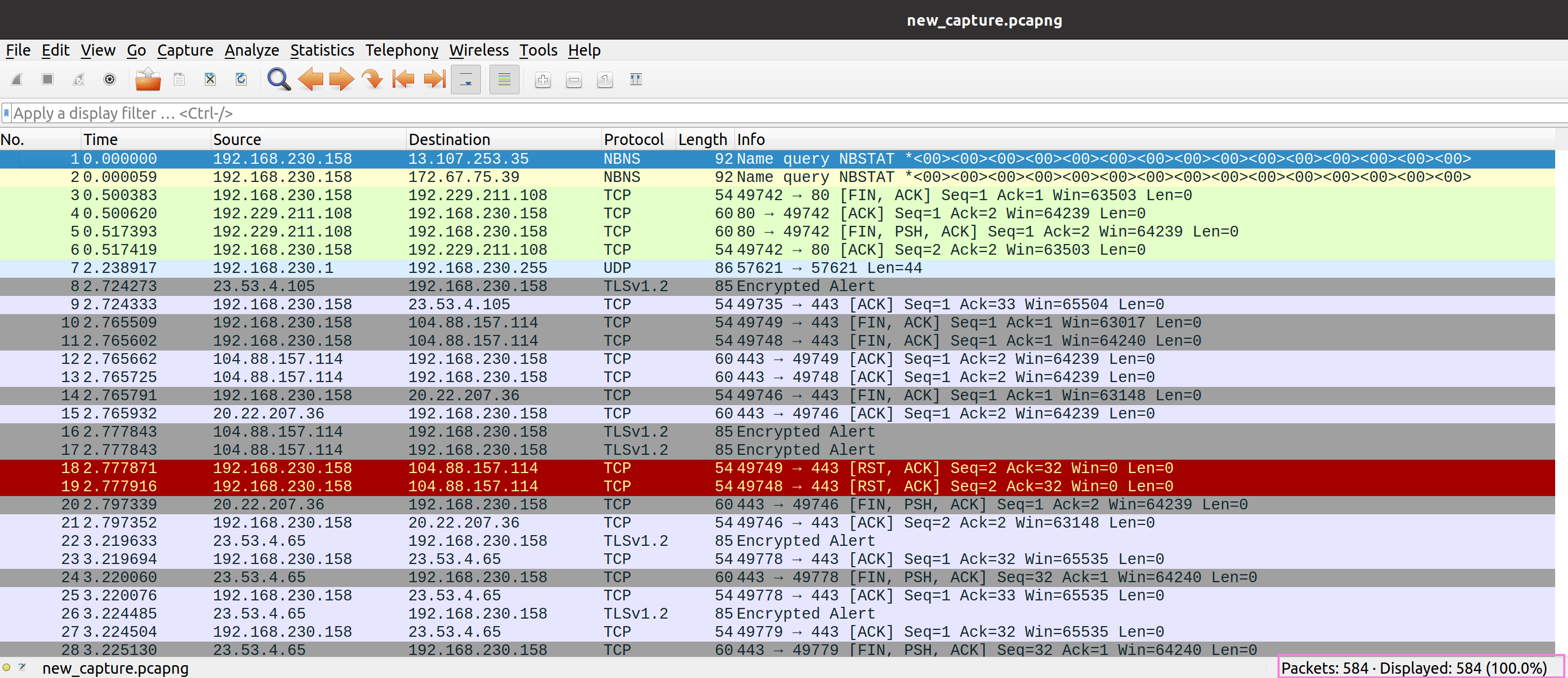

So let’s have a quick look at what’s going on in the packet capture. Open your Ubuntu VM, open WireShark, and then open the packet capture we transferred over in Section 5.1. You should see something along the lines of the following, though of course remember again our results won’t be identical.

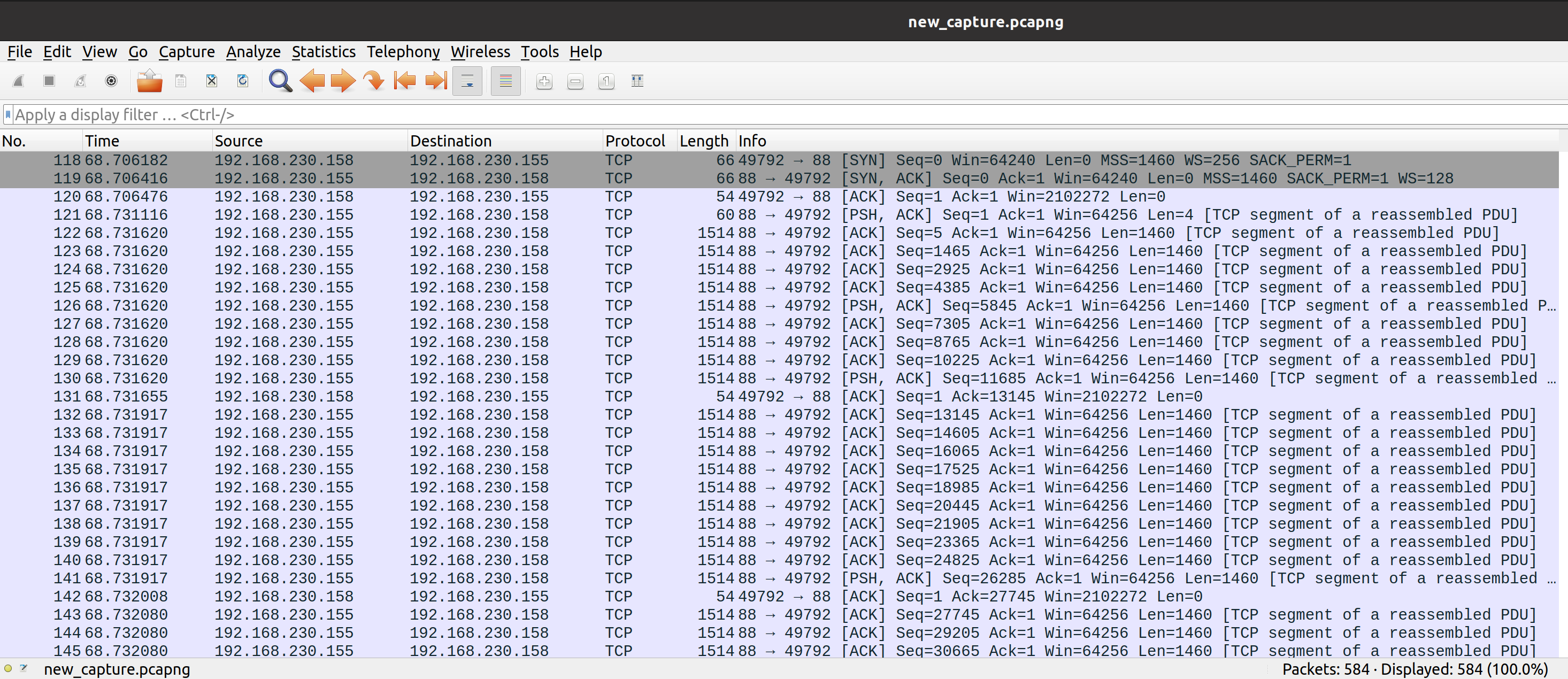

We can see that in the brief amount of time we ran the capture for a total of 584 packets were captured. In case you are completely new to this: we can expect a lot of these to be completely unrelated to our attack. Even if you are not even interacting with your system it typically generates a lot of packets via ordinary backend operations.

So, our next step would now be to find which packets are related to the emulated attack.

Scrolling down, in my capture we can see around packet 58 + 59 there is a DNS request + response for raw.githubusercontent.com.

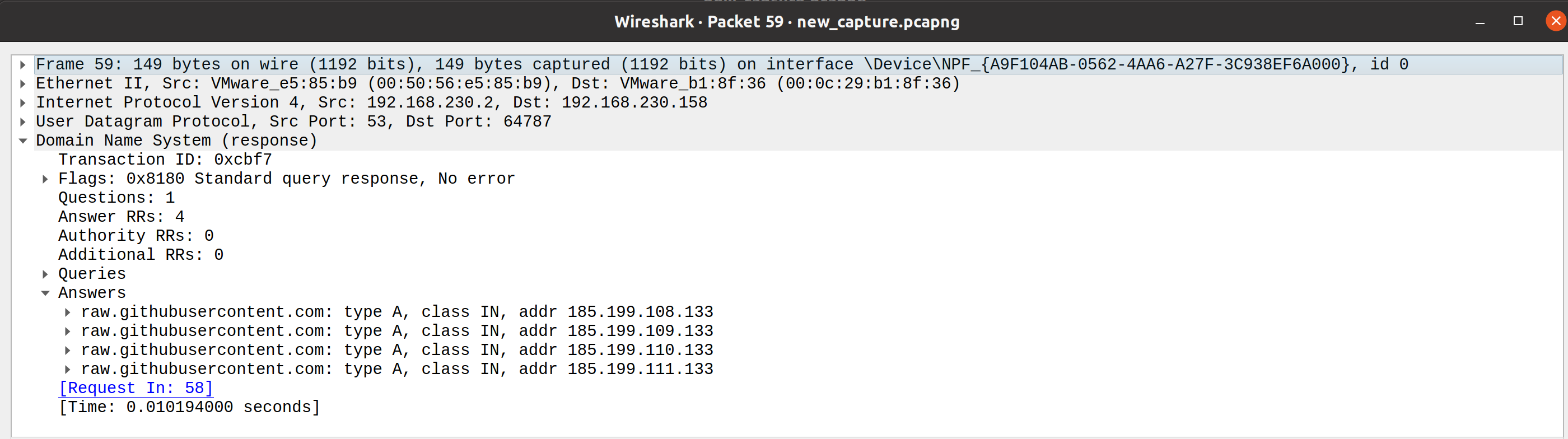

This is of course where the initial IEX command (representing our stager) reached out to that specific web server to download the injection script. Double-click on the second packet (the response), then in packet details select Domain Name System (response), and then Answer.

Here we can see the IPs the FQDN resolves to - again, in an actual attack we can immediately run this IOC to see for example what other systems connected to it, is it present on any threat intelligence blacklists etc.

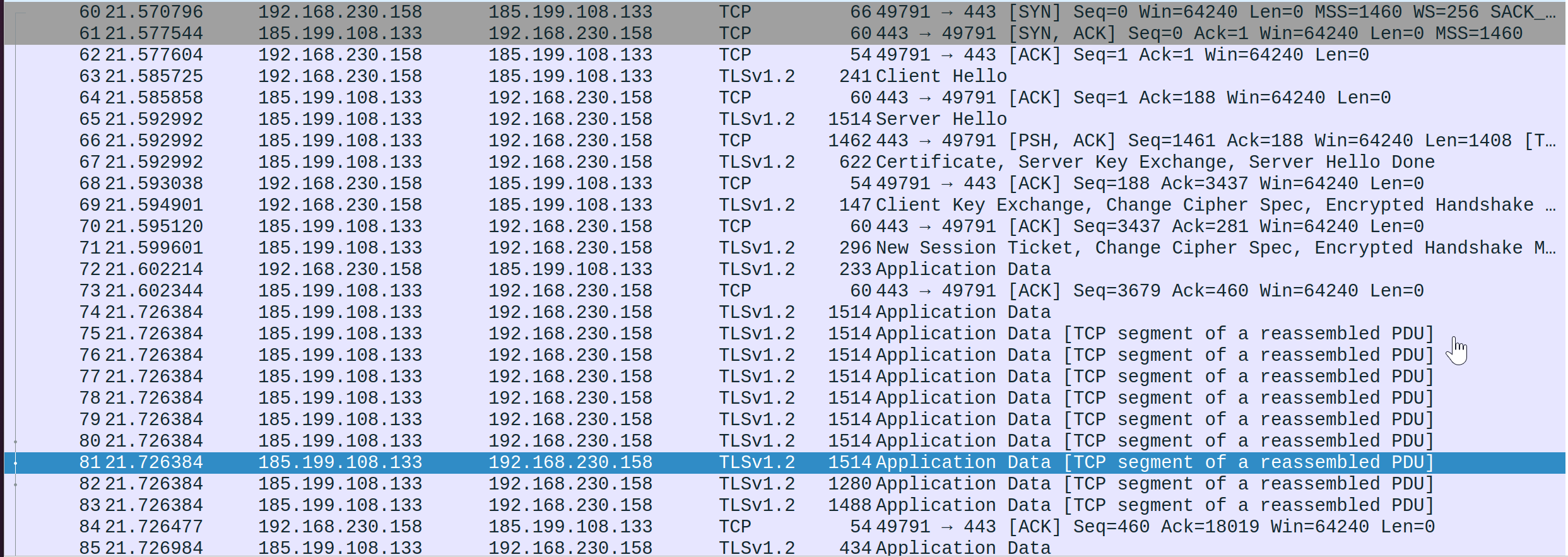

Immediately after the DNS we can see the conversation taking place between our system and the web server - first the certificates are being authenticated, then an encrypted (TLS) exchange takes place. This is likely the actual injection script being downloaded. Since it is encrypted we cannot easily view the contents, however we already saw that the entire script that was download is accessible via PowerShell ScriptBlock logs.

And then, around packet 118, we can see the connection being established between our system and the attacker.

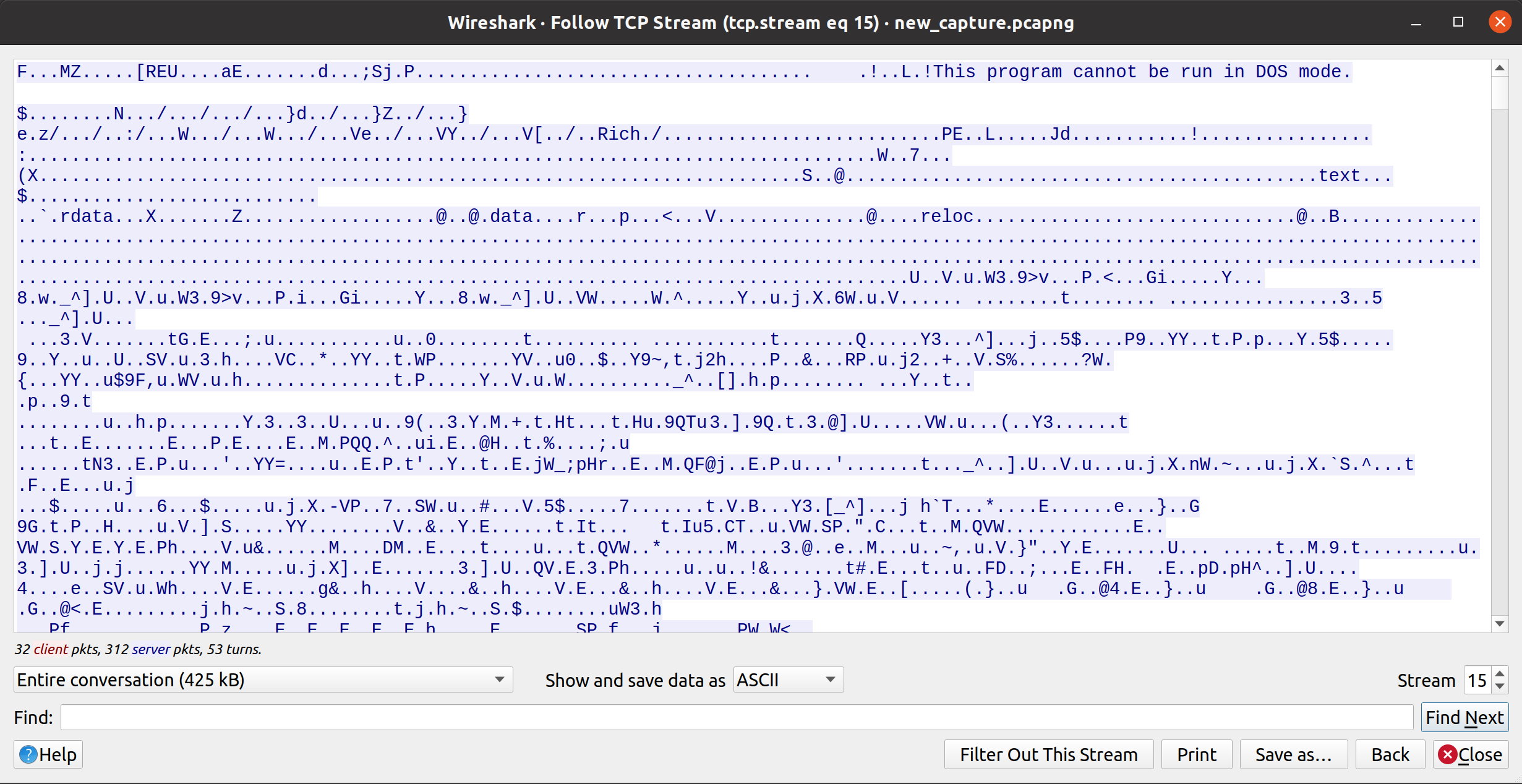

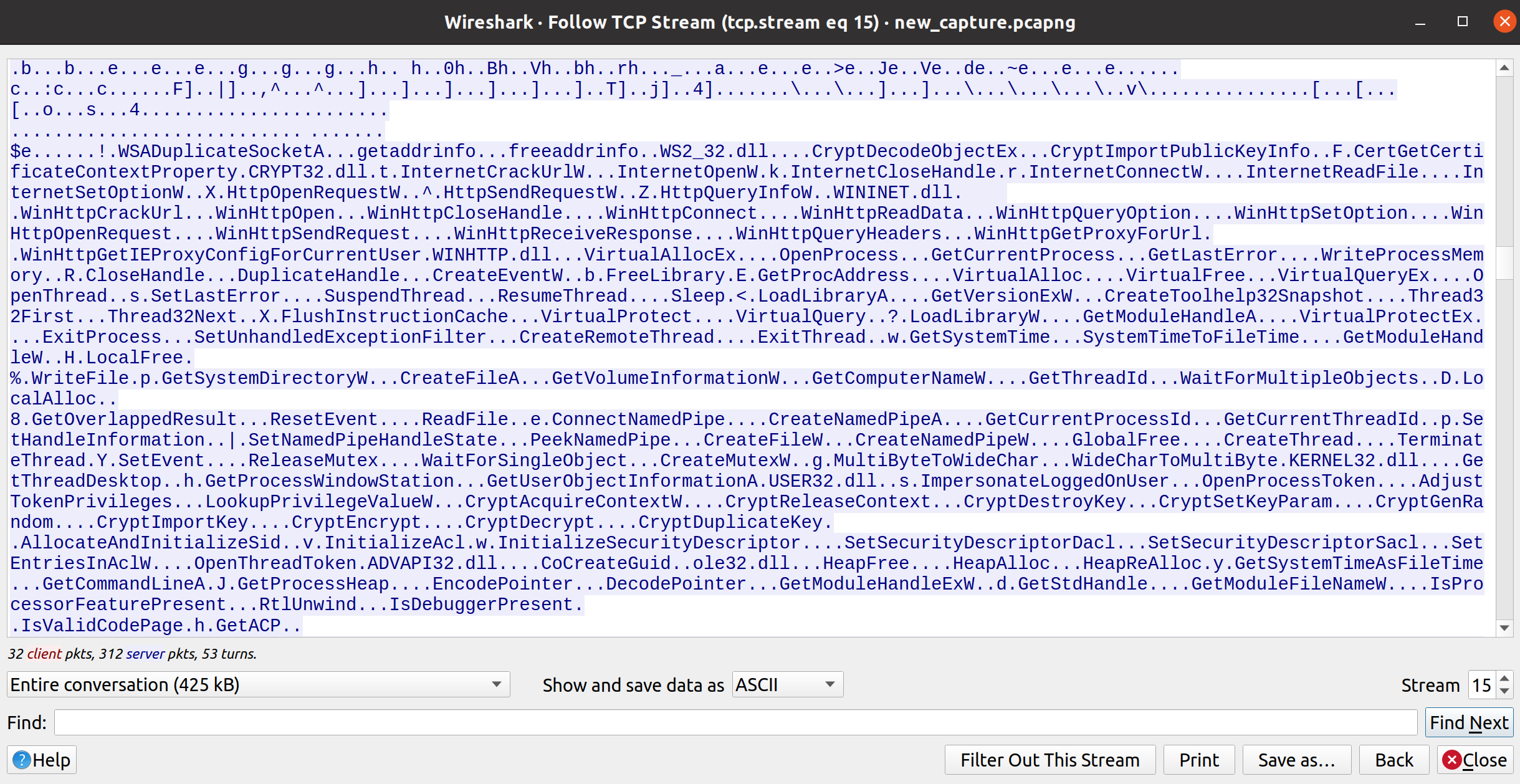

This represents a few hundred packets. In these cases, the easiest way to get a feel for what is being exchanged is to right-click on any packet (part of this series), then select Follow, TCP Stream. This shows the entire stream of contents that was exchanged.

Right at the top we see something interesting and familiar - the magic bytes and the dos stub! This should thus give us a good hint at what we are looking at here. For the rest we can see most of the content is encrypted/obfuscated, but here and there we do see some clear text appearing.

There are thus many interesting questions we can ask based on what we are witnessing here, which may lead us to find out what mechanisms the malware is employing. Without getting into it too deeply, as a simple example when I Google the term Copyright 1995-1996 Mark Adler (which appears in the stream), we immediately find out this is due to zlib being included in the code. Thus it’s likely the payload is being compressed or obfuscated using zlib, which itself is of course a completely legitimate data compression software.

In any case, these are simply speculative musings. As I’ve said before - we’ll wait till a future course before peering under the malware hood.

That being the case, this is where we’ll end our traffic analysis - short and sweet. As I said, the idea here was just to give you some idea of what it entails. Rest assured that in a future course you will get much better acquainted with this powerful modality. I’m looking forward to it - it’s gonna be awesome!

| Course Overview | Return to Section 6 | Proceed to Section 8 |