Section 4: Live Analysis - Process Hacker

| Course Overview | Return to Section 3 | Proceed to Section 5 |

4. Live Analysis: Process Hacker

4.1. Introduction

I explained, hopefully in a somewhat convincing manner, why it’s good practice for us to learn how to use the native Windows tools to get an initial, high-level read. But of course these tools are also limited in what information they can provide.

So now let’s bring out the big guns and learn all we can.

As these things go, it really behooves us to learn a bit of theory behind what we’re going to look at with the intention of understanding why it is we are looking at these things, and what exactly we will be looking for.

4.2. Theory

“A traditional anti-virus product might look at my payload when I touch disk or load content in a browser. If I defeat that, I win. Now, the battleground is the functions we use to get our payloads into memory. -Raphael Mudge”

There are a few key properties we want to be on the lookout for when doing live memory analysis with something like Process Hacker. But, it’s very important to know that there are NO silver bullets. There are no hard and fast rules where if we see any of the following we can be 100% sure we’re dealing with malware. After all, if we could codify the rule there would be no need for us as threat hunters to do it ourselves - it would be trivial to simply write a program that does it automatically for us.

Again we’re building a case, and each additional piece of evidence serves to decrease the probability of a false positive. We keep this process up until our threshold has been reached and we’re ready to push the big red button.

Additionally, the process as outlined here may give the impression that it typically plays out as a strictly linear process. This is not necessarily the case - instead of going through our list 1-7 below, we could jump around not only on the list itself, but with completely different techniques.

As a simple example - if we find a suspicious process by following this procedure, we might want to pause and have the SOC create a rule to scan the rest of the network looking for the same process. If we for example use Least Frequency Analysis and we see the process only occurs on one or two anomalous systems, well that then not only provides supporting evidence, but also gives us the confirmation that we are on the right path and should continue with our live memory analysis.

Here’s a quick overview of our list:

- Parent-Child Relationships

- Signature - is it valid + who signed?

- Current directory

- Command-line arguments

- Thread Start Address

- Memory Permissions

- Memory Content

Let’s explore each a little more:

- Parent-Child Relationships

As we know there exists a tree-like relationship between processes in Windows, meaning an existing process (parent), typically spawns other processes (child). And since in the current age of Living off the Land malware the processes themselves are not inherently suspicious - after all they are legit processes commonly used by the system - we are more interested in the relationship between processes. We should always ask: what spawned what?

We’ll often find a parent process that is not suspicious by itself, or equally, that viewed in isolation is completely routine. But the fact that this specific parent spawned that specific child - we’ll sometimes that’s the thing that’s off.

And of course we’ve already encountered this exact situation in the previous section with neither rufus.exe nor rundll32.exe being suspicious, but the fact that the former is spawned the latter being unusual.

Something else worth being aware of is not only may certain parent-child relationships indicate that something is suspicious, but the specifics can act as some sort of signature implying what malware is involved.

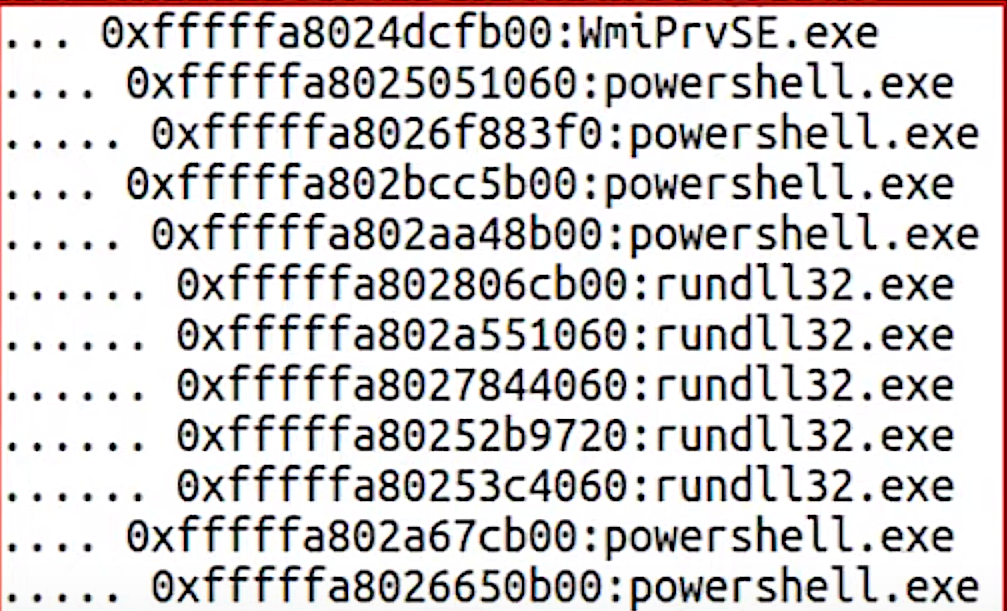

For example a classical Cobalt Strike process tree might look like this:

At the top we can see WMI spawning PowerShell - that itself is pretty uncommon, but used by a variety of malware software. But there’s more - PowerShell spawning PowerShell. Again, not a smoking gun, but unusual, and something seen with Cobalt Strike.

But really the most idiosyncratic property here is the multiple instances of rundll32.exe being spawned. This is classical Cobalt Strike behavior - the use of so-called sacrificial process. Plus the fact that it’s rundll32.exe in particular - using this process name is the default setting for Cobalt Strike.

It might surprise you but in situ it’s estimated that about 50% of adversaries never bother changing the default settings. Which makes one wonder - are they lazy, or are we so bad at detecting even default settings that they don’t see the point in even bothering?

All this to say - we’ll look for unusual parent-child Relationships, and we’ll do so typically by looking at a process tree which shows as all processes and their associated relationships. In the discussion above I might have given the impression that these relationships all exist in pairs with a unidirectional relationship. Not so, just as in actual family trees a parent can spawn multiple children, and each of these can in turn spawn their own children etc. So depending on the exact direction of the relationship, any specific process may be a parent or a child.

- Signature - is it valid + who signed?

This is definitely one of the lowest value indicators - something that’s nice to help build a case, but by itself, owing to so many potential exceptions, is frankly useless. Nevertheless it is worth being aware of - whether the process is unsigned, or signed by an untrusted source.

- Current directory

There are a number of things we can look for here. For example we might see a process run from a directory we would not expect - instead of svchost.exe running from C:\Windows\System32, it ran from C:\Temp - UH-OH.

Or, perhaps we see PowerShell, but it’s running from C:\Windows\Syswow64\..., which by itself is a completely legitimate directory. But what exactly is its purpose?

It essentially indicates that 32-bit code was executed. While 32-bit systems are still in use, the majority of contemporary systems are 64-bit. However, many malware programs prefer using 32-bit code because it offers broader compatibility, allowing them to infect both 32-bit and 64-bit systems.

So if we saw PowerShell running from that directory, it means that a 32-bit version of PowerShell ran on a 64-bit OS, which is not what we expect in ordinary circumstances.

- Command-line arguments

We already saw this in the previous section - for example though running rundll32.exe is completely legit, we would expect it to have arguments referencing the exact function and library it’s supposed to load. Seeing it nude, well that’s strange.

Same goes for many other processes - we need thus to understand their function and how they are invoked to be able to determine the legitimacy of the process.

- Thread Start Address

When a DLL is loaded in the traditional way, ie from a disk, the operating system memory-maps the DLL into the process’s address space. Memory mapping is a method used by the operating system to load the contents of a file into a process’s memory space, which allows the process to access the file’s data as if it were directly in memory. The operating system also maintains a mapping table that tracks where each DLL is loaded in memory.

With traditional DLL loading, if you were to look at the start address of the thread executing the DLL, you would see some memory address indicating where the DLL has been loaded in the process’s address space.

However, in the case of Reflective DLL Injection, the DLL is loaded into memory manually without the involvement of the operating system’s regular DLL-loading mechanisms. The custom loader that comes with the DLL takes care of mapping the DLL into memory, and the DLL never touches the disk. Since the operating system isn’t involved in the process, it doesn’t maintain a mapping table entry for the DLL, and as such, the start address of the thread executing the DLL isn’t available.

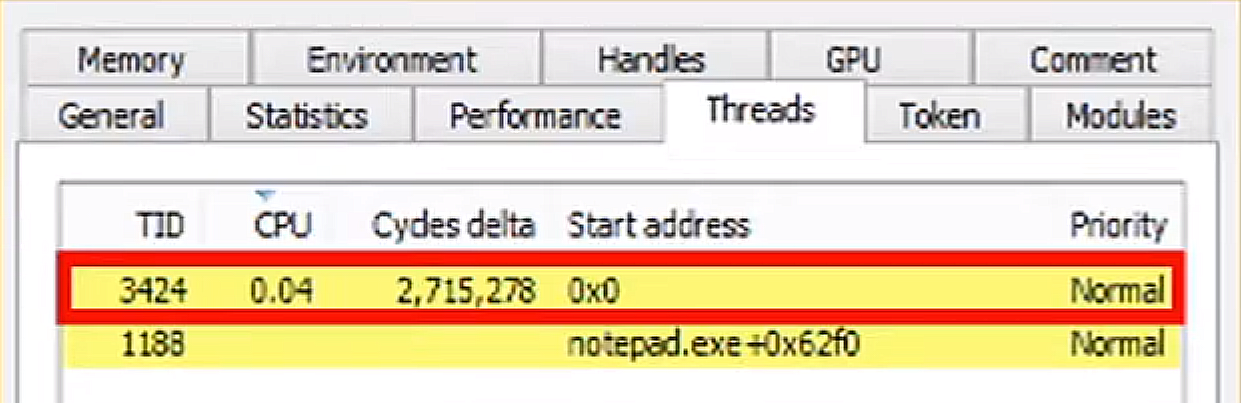

As a result, when you inspect the start address of the thread associated with the injected DLL, it will not show the actual memory address where the DLL is loaded. Instead, it will show 0x0, which essentially means the address is unknown or not available - see image below. This is one of the many ways Reflective DLL Injection can be stealthy and evade detection.

- Memory Permissions

One of the most common, well-known heuristics for injected malware is any memory region with RWX permissions. Memory with RWX permissions means that code can be written into that region and then subsequently executed. This is a capability that malware often utilizes, as it allows the malware to inject malicious code into a running program and then execute that code. The vast majority of legitimate software will not behave in this manner.

But be forewarned - RWX permissions are the tip of the iceberg in this game of looking for anomalies in memory permissions.

Modern malware authors, knowing RWX not only sticks out like a sore thumb but can easily be detected with a Write XOR Execute security policy, might instead create malware to have an initial pair of permissions (RW), which will then afterwards change permissions to RX.

I wanted you to be aware of this, but for now we will focus only on RWX.

- Memory Content

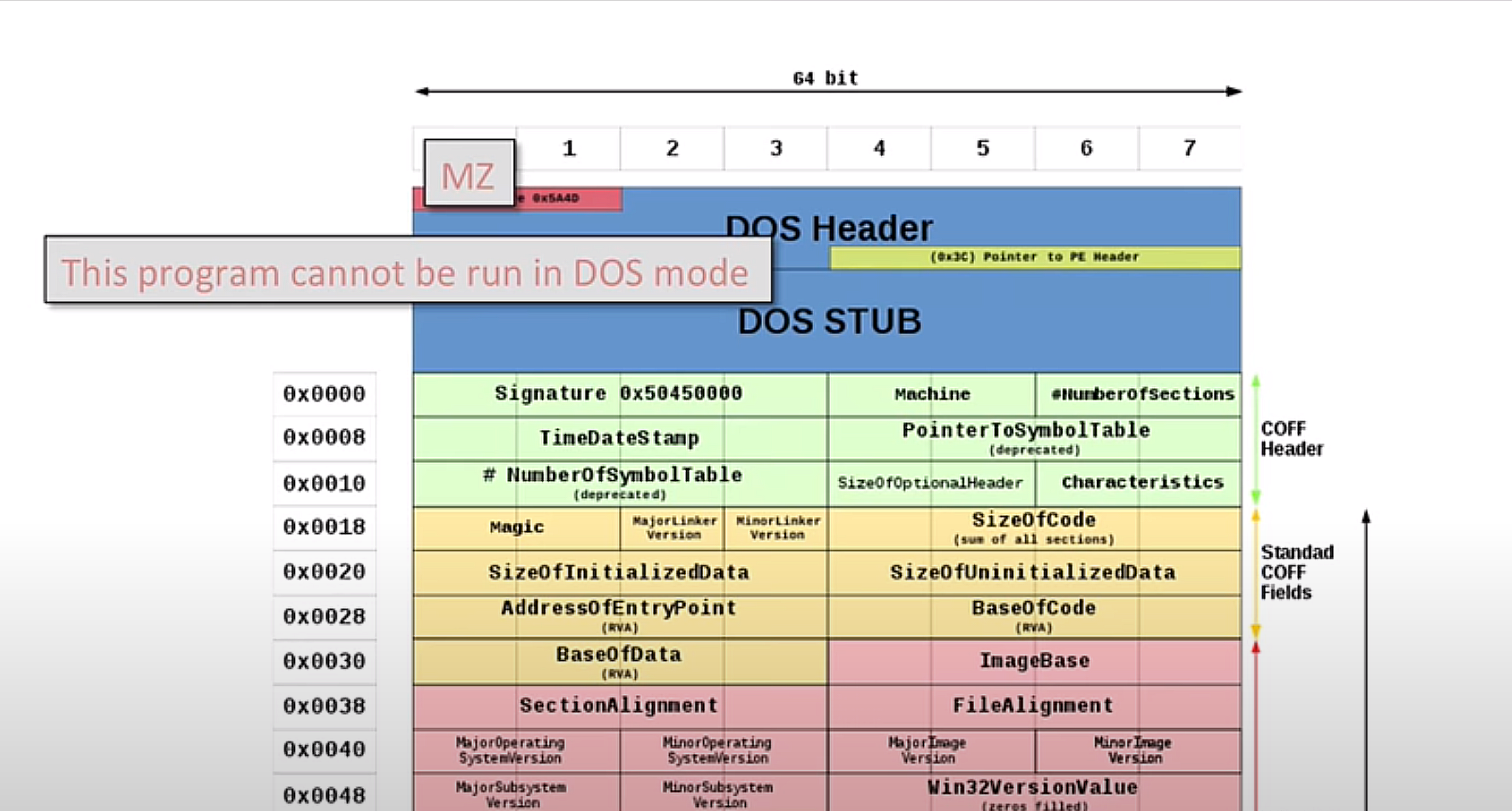

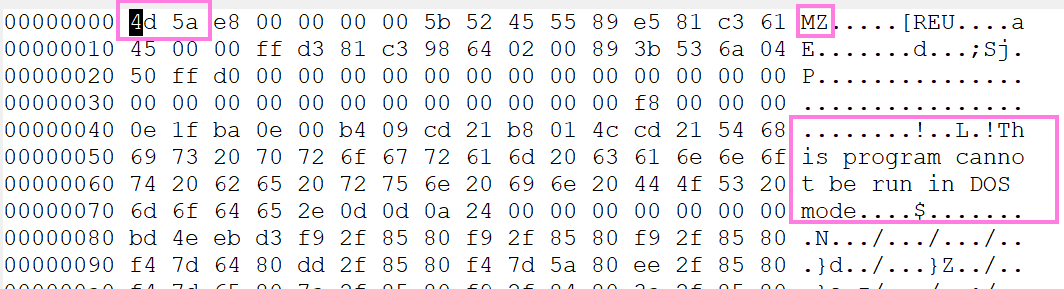

Once we find a memory space with unusual permissions we then also want to check its content for signs of a PE file. Let’s quickly have a look at a typical PE file structure:

We can see two things that always stick out: the magic bytes MZ and a vestigial string associated with the DOS Stub. Magic bytes are predefined unique values used at the beginning of a file that are used to identify the file format or protocol. For a PE file, we would expect to see the ASCII character MZ, or 4D 5A in hex.

Then the string This program cannot be run in DOS mode is an artifact from an era that some systems only ran DOS. However the string is still kept there, mainly historical reasons. For us in this case however it’s a useful thumbprint, informing us we’re dealing with a PE file.

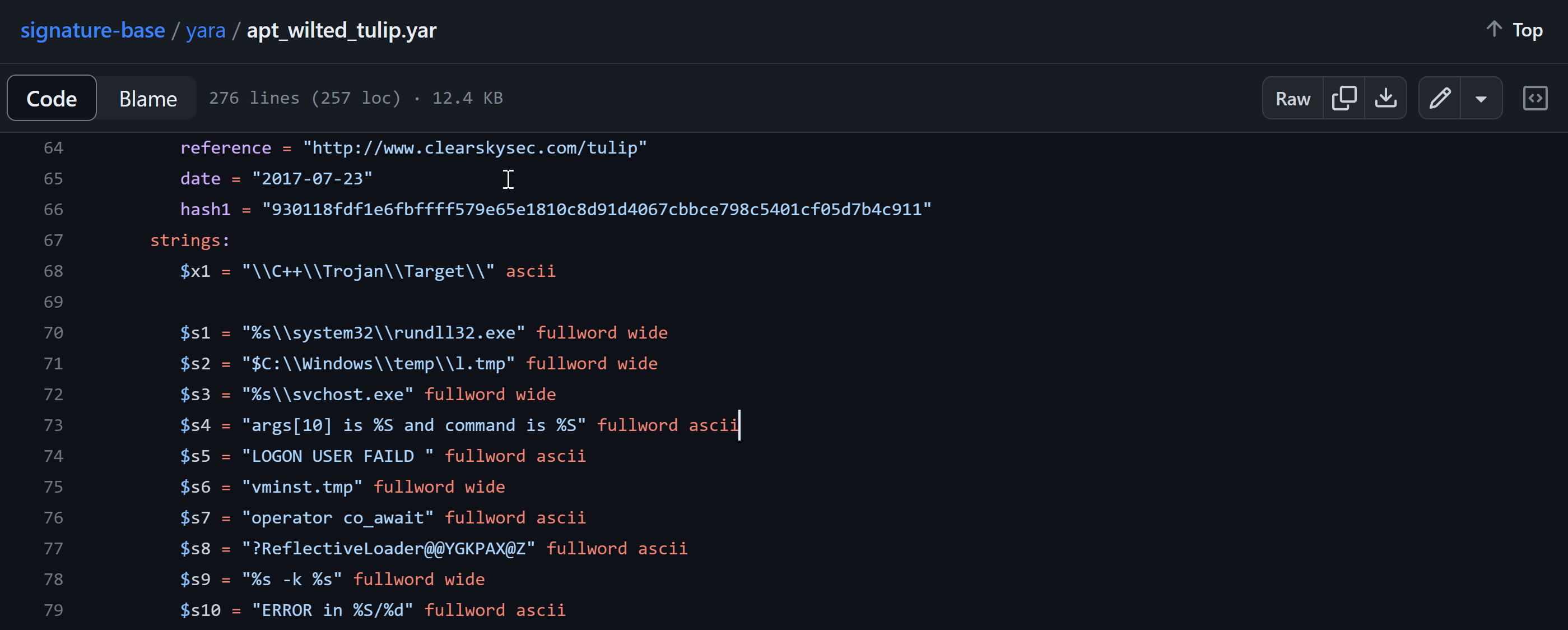

Further, in the rest of the contents we might be able to find some strings that are associated with specific malware. And typically, rather than trudging it manually we can automate the process using YARA rules.

For example below we can see Yara rules authored by Florian Roth for Cobalt Strike. The image shows a number of string-based rules it would be looking for - all indications that the PE file is part of a Cobalt Strike attack.

Finally it’s worth being aware of PE Header Stomping - a more advanced technique used by some attackers to avoid detection. As another great mind in the Threat Hunting space, Chris Benton, likes to say: “Malware does not break the rules, but it bends them”.

PE files have to have a header, but since nothing really forces or checks the exact contents of the header, the header could theoretically be anything. And so instead of the header containing some giveaways like we saw above - magic bytes, dos stub artifact, signature strings etc - the malware will overwrite the header with something else to appear legitimate. For now I just wanted you to be aware of this, we’ll revisit header stomping first-hand in the future.

But for now, that’s it for the theory - allons-y!

4.3. Analysis

Open Process Hacker as admin - ie right-click and select Run as administrator. Scroll down until you see rufus.exe (or whatever other legitimate process you chose to inject into). Let’s go through our 7 indicators.

- Parent-Child relationships

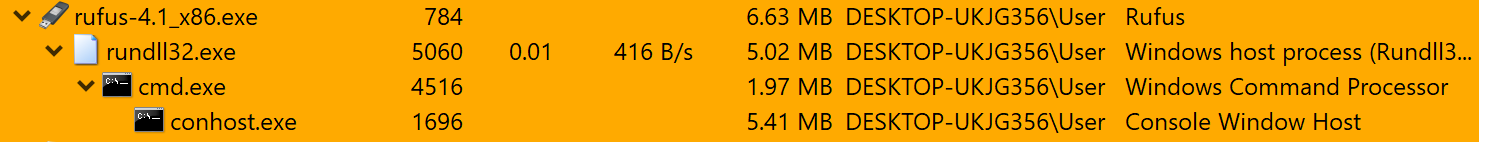

We can immediately see the same suspicious process and parent we saw in our analysis using native tools - there is the legitimate process rufus.exe, which unexpectedly spawned the child process rundll32.exe.

But then we see something else we forgot to consider in our previous analysis - has rundll32.exe itself spawned anything in turn? Indeed rundll32.exe has in turn spawned cmd.exe.

I mentioned before that rundll32.exe is typically used to launch DLLs. There is thus little reason for us to expect it to be spawning the Windows command line interpreter cmd.exe. Now it could be that some amateur developer wrote some janky code that does this as some befuddling workaround, but that’s steelmanning it to the n-th degree.

We’re not ringing the alarm bells yet, but we’re definitely geared to dig in deeper.

Let’s double-click on the process rundll32.exe…

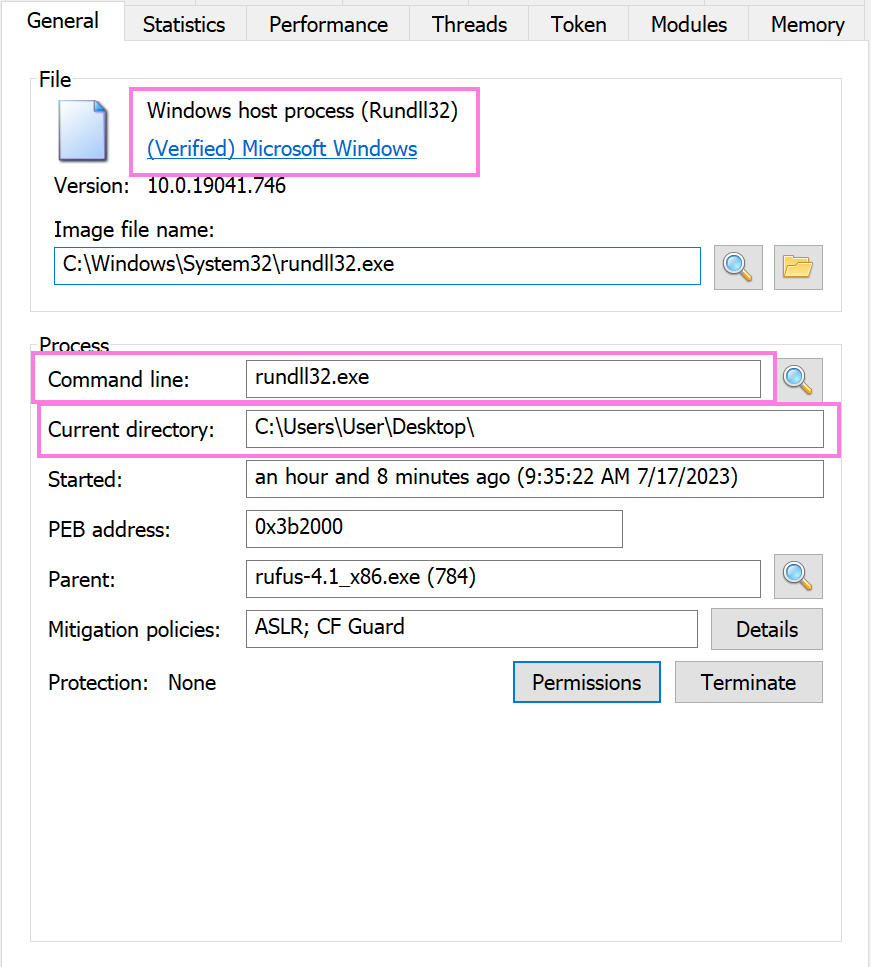

- Signature - is it valid + who signed?

We can see here that it has a valid signature signed by Microsoft, since of course they are the creators of rundll32.exe. Nothing further to concern ourselves with here.

- Current directory

In the same image, we can see the Current directory, which is the “working directory” of the process. This refers to the directory where the process was started from or where it is currently operating. We can see here that the current directory is the desktop, since that’s where it was initiated from.

Now this could happen with legitimate scripts or applications that are using rundll32.exe to call a DLL function. However, seeing rundll32.exe being called from an unusual location like a user’s desktop could be suspicious, particularly if it’s coupled with other strange behavior.

- Command-line arguments

And again in reference to the same image we once more we see that the Command-line is rundll32.exe. We already saw this before where I discussed why this is suspicious - we expect rundll32.exe to be provided with arguments.

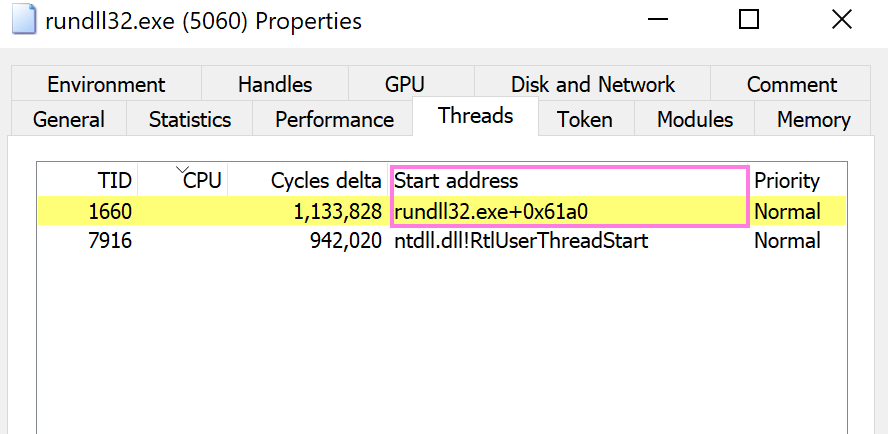

- Thread Start Address

On the top of the Properties window select the Threads tab.

We can see under Start address that it is mapped, meaning it does exist on disk. This essentially tells us that this is not a Reflectively Loaded DLL, since we would expect that to have an unknown address listed as 0x0.

- Memory Permissions

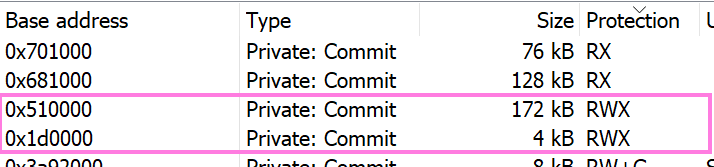

On the top of the Properties window select Memory. Now click once on the Protection header to sort it. Scroll down until you see RWX permissions.

Indeed we see the presence of two memory spaces with Read-Write-Execute permissions, which as we learned is always suspicious since there are very few legitimate programs that will write to memory and then immediately execute it.

- Memory Content

Finally let’s double-click on the larger of the two (172 kB) since this typically represents the payload.

We immediately see the two clear giveaways that we are dealing with a PE file. We can see the magic bytes (MZ), and we see the strings we associate with a PE Dos Stub - This program cannot be run in DOS mode. Again, another point for “team sus”.

That’s it for our live memory analysis: feel free to exit Process Hacker. Let’s discuss our results before moving on to our post-mortem analysis.

4.4 Final Thoughts

Let’s briefly review what we learned in this second live analysis using Process Hacker.

We came into this with a few basic breadcrumbs we picked up in our live analysis using the native tools:

- A process,

rundll32.exe, created an unusual outbound connection. - This process had an unexpected parent process,

rufus.exe. - The process was ran without the command-line arguments we would expect it to have.

This thus then set us off to dig deeper into this unusual process using Process Hacker:

rundll32.exeitself spawnedcmd.exe- very suspicious.rundll32.exewas ran from the desktop - unusual.- The process also had

RWXmemory space permissions, which is a big red flag. - We saw that the memory content of the

RWXmemory space contained a PE file - again, red flag.

This signifies the end of our live analysis, ie analysis we perform with the suspicious process still being active. We’ll now move onto post-mortem analysis to see what else we can learn from the suspicious process.

At this point keep your Windows VM on, shut down your Kali VM, and turn on your Ubuntu VM.

| Course Overview | Return to Section 3 | Proceed to Section 5 |